Planning for Success Is Harder (Than Planning for Regret)

Life just flies by. One minute we are scolding a five-year-old, and the next we are attending their college graduation. One minute we are the perfect weight, and 10 years later, we are 15 pounds overweight. One minute we should make a call on a chip in the windshield, and a month later, it has turned into a big crack. One minute we maintain caution about markets, and months later we have missed out on some likely easy returns. In all these scenarios, our good intentions and human nature get in the way of better outcomes. To improve our results, we must recognize how our fallibility can come at a cost.

Before I move on, a quick note about what I am writing about. This is not an article about staying invested for the long term per se. Most people understand that is smart to do if you want to let compounding returns make you the most money. I will tip my hat to my fellow Gen Xers here and remind them to always remain skeptical but stay 100% invested. Instead, this article is more about pulling the trigger on investing cash, as I find that decision is often harder than any other decision in investing.

Do You Plan for Success or Plan to Minimize Regret?

In the 2013 film We’re the Millers, the father figure, David (Jason Sudeikis), is sharing his key to success with his make-believe son Kenny (Will Poulter). Kenny asks how David makes tough decisions, and David says it’s easy: Just count to three and do what you know you need to do. David explains that if you think longer than three, you will not do it.

David’s method may sound flimsy, particularly when thinking about financial decisions. Yet I would argue that overthinking something more often gets in the way. Overthinking is potentially more about minimizing regret versus planning for success. I’ll explain using the current stock market as an example.

What Isn’t Going to Change? Think the Opposite

I will start with the premise that someone has a well-thought-out asset allocation that matches their long-term goals. If that is true, then the first step of investing cash, especially when it might be a large sum (e.g., business sale proceeds, inheritance, stock option exercise), is acknowledging that success is aspirational, but biases feel real.

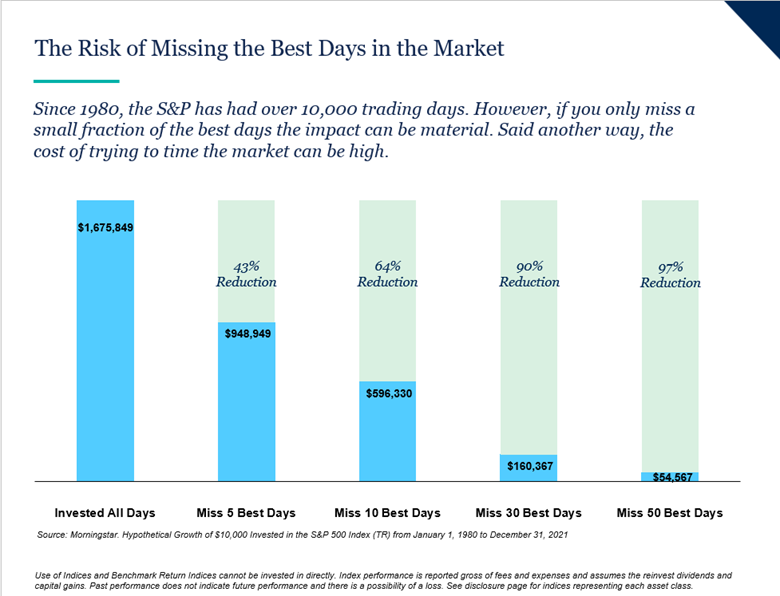

Success is aspirational in investing; it is only measured decades into the future and usually by a fairly easy metric (i.e., did you run out of money). But long before you can get those results, you must take the leap today to get invested. Near-term biases like anchoring (“I’ll get invested when I see X happen”) or recency (the economy looks weak or markets are volatile right now) feel more concrete than the future of compounded returns. This illusion of control is costly, though, as this chart shows:

This chart suggests that there are only a certain number of trading days in a year where we make money. Trying to guess those days is fruitless. It is always somewhat surprising to me, for example, that missing just the five best days since 1980 would have cost someone 43% lower account balances (assuming just being invested in the S&P 500 during this time).

It might seem like a wise move to wait and see what the Fed is going to do with interest rates, whether we fall into a recession, whether unemployment ticks up, whether commercial real estate falters—or a slew of other things. The problem with that approach is summarized:

Half of the S&P 500 Index’s strongest days in the last 20 years occurred during a bear market. Another 34% of the market’s best days took place in the first two months of a bull market—before it was clear a bull market had begun. In other words, the best way to weather a downturn could be to stay invested since it’s difficult to time the market’s recovery.

- Source: Ned Davis Research, 12/21. Time period referenced is 12/16/01–12/15/21.

Timing the market just doesn’t work. Time in the market does.

Today’s Real-Life Example

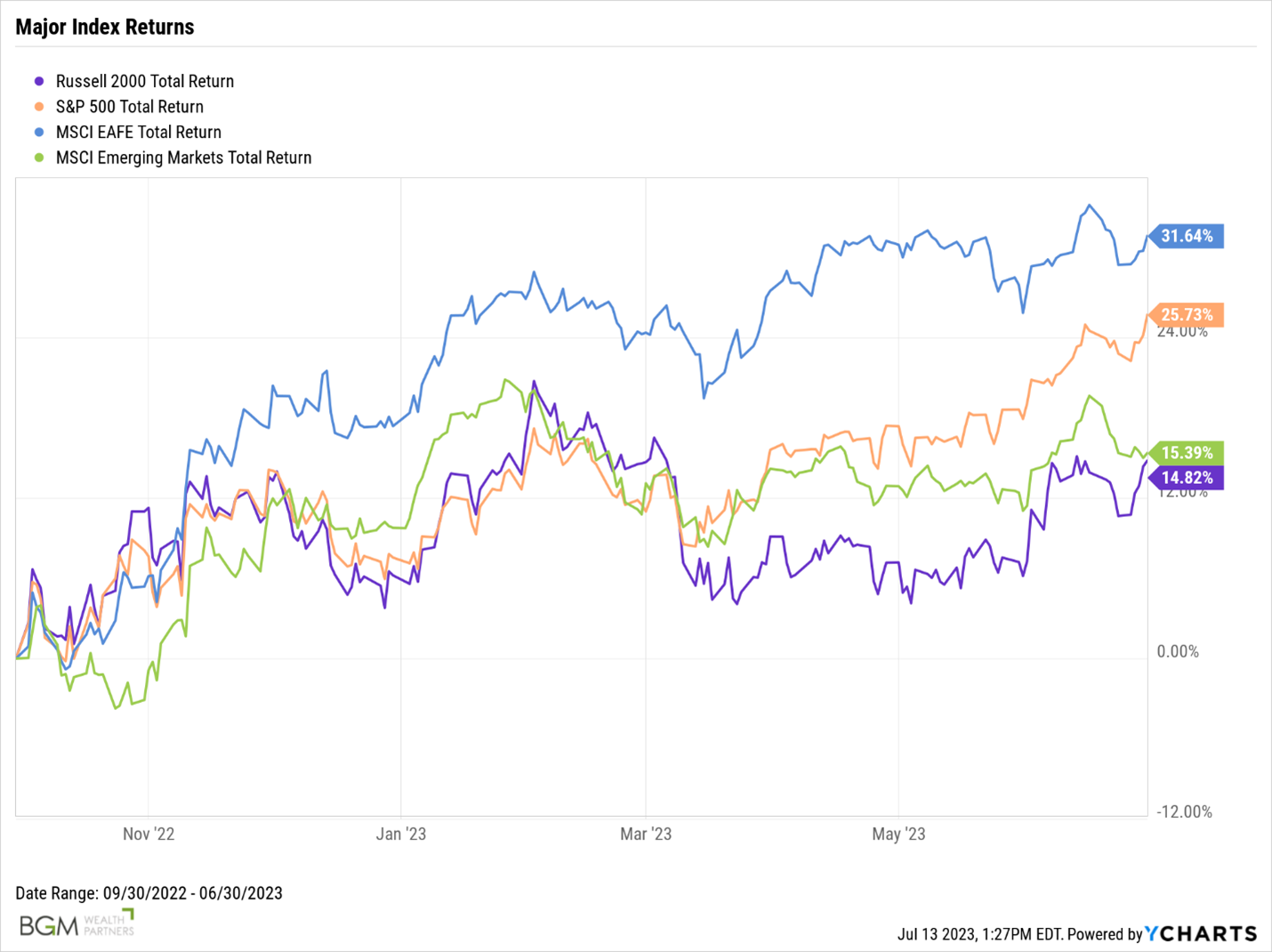

Just in case you haven’t looked under the hood of today’s market, here is the performance since September 30, 2022, thru June 30, 2023 (I picked September because that is near the lows for last year and since then the markets have generally moved up):

Depending on the index chosen (I am only showing stocks, not bonds; a diversified portfolio would have a lower blended return than investing in just one index), the reality is that sitting in cash over the last nine months had an opportunity cost (of course, past performance is not indicative of future results).

There is no guarantee this performance sticks, but it does suggest that my earlier comments about missing the best days, maybe particularly in a bear market, can lead to underperformance that is measurable.

To be fair, we are still below the highs of the markets reached in 2021. But waiting to verify we are back to that point means missing out on what I would consider the easiest part of investing. We all spend a lot of time in life trying to maximize results (i.e., guess perfectly) when the easiest way to do that is to simply have a seat at the table. Even if you are wrong in the near term, long-term results probably get you to 80% of your goal, whereas sitting on the sidelines gets you a lot less than that.

In the End …

I can pick any time frame and produce a chart that tells the story of how people make decisions that work against their own best interests. Usually, that means they got out of the market due to worry or did not invest cash into the market because of worry. Notice, “worry” is the word I use because worry is not measurable and is more in line with minimizing regret.

Investing today, particularly if you are sitting on cash, is a vote for better days to come—a skill that Warren Buffett constantly reminds us Americans that we excel at.

If you have questions or would like to learn more, contact Jon Meyer, CFP® at jmeyer@bgmwealth.com or send us a message.

The opinion of the author is subject to change without notice and must be considered in conjunction with relevant regulation, as well as subsequent changes in the marketplace. Any information from outside resources has been deemed to be reliable but has not necessarily been verified. Each individual has unique circumstances to which this information may or may not be relevant. Under no circumstances will this information constitute an offer to buy or sell and it does not indicate strategy suitability for any particular investor.